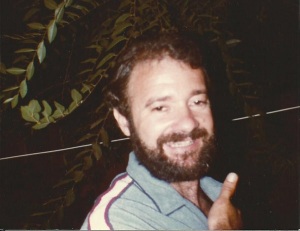

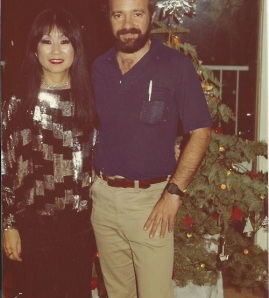

Kathy Green was raised in St. Louis, Missouri. After majoring in geology, she became a National Park Ranger for five years. During that time, she met Chuck Kroger [the editor’s brother], whom she married in 1978. They settled in Telluride, Colorado in 1979, where they co-founded Bone (Back of Nowhere Engineering) Construction company. When Chuck died of pancreatic cancer in 2007, Kathy and co-workers continued the company’s projects. Kathy enjoys hiking, running rivers, making art (including silk dying), and working for environmental and social justice in her region.

Background: Missouri was the compromise state in the Civil War. Some of my great great great ancestors fought on the confederate side and owned slaves. My mother still has the slave book from that time, recording the births and deaths of the slaves. My mother also was told (oral history) that my fifth great grandfather was a “good owner” because he never broke up families.

I was in first grade in 1956 when Adlai Stevenson was running for president. My family had moved to Webster Groves a year earlier. Webster Groves, a St. Louis suburb, was more conservative and Republican than my family. My understanding is that all of my family had been Democrats since the Democratic Party was formed in the 1830s. A few family “rogues” have married Republicans but their kids have all been born Democrats. I came home in tears one day in late October 1956 because we had had a mock election at school. Out of 30 students in my class, Adlai Stevenson had gotten only six votes. Come election day that November, I was “working the election”—almost six years old, standing the required 100 feet from the door to the school/polling-place door, smiling and trying to hand every approaching voter a Stevenson brochure. Working elections was a family activity. A little metal pin of the bottom of a shoe with a hole worn in the sole is one of my prize possessions to this day. Go Adlai!

At the same time that I was a young child being taught to work elections and work to preserve historic buildings from demolition, my grandfather, John Raeburn Green, and the family law firm were under severe criticism and lost many clients during the McCarthy witch-hunt. My grandfather believed that everyone deserved counsel and he believed in free speech. He took the pro bono case of a man accused of being a Communist and defended him before the Supreme Court (and lost). For that volunteer work, Joseph McCarthy, from the Senate floor, called my grandfather and his law partner (one of the senators from Missouri) communists—a scary and destructive event at the time. Many of my family preferred to be activists that flew “under the radar” after that experience. We were never afraid to be Democrats, to work for social justice, environmental justice, and other liberal causes. We just did not need recognition—especially in the Senate. I didn’t understand the risk completely. I don’t think even my grandfather understood it that well. But I grew up my entire life with this story. My mother said never to tell anyone you were a socialist or a communist.

When I was five, my kindergarten teacher taught us the National Anthem and Dixie, one right after the other. One time when my family went to a ball game, everyone stood and sang the National Anthem. When it was over I started in to sing Dixie. My mom asked what on earth I was doing, and I said, Singing the next stanza. She said, No! Can’t you tell that those are two different songs? I couldn’t; apparently I’m tone-deaf/musically challenged. Throughout elementary school our music teacher had us sing both songs in succession.

Our family were big Hubert Humphrey supporters. Once John Kennedy became the Democratic candidate for President, we were all for him. We worked hard to help Kennedy win the election. Many of our friends were Republicans so during the 1960 election and during his presidency, I heard these friends rant and rave against JFK. On Nov. 22, 1963, I was almost 13 years old and in eighth grade. They told us over the junior high school speaker system that President Kennedy had been shot in Dallas. School was dismissed. I walked out of school confused and upset, into a howling rainstorm. As I tried to find the friends that I usually walked to and from school with, my mother suddenly appeared with my little brother to drive me home. Everyone was crying. At home, the TV was on full time—that never happened in our house; we traditionally watched only an hour or two of TV a day. All our friends came by our house over the next few days. The people that had been ranting and raving against Kennedy were crying and praising him. I found this total change in their feelings startling and confusing.

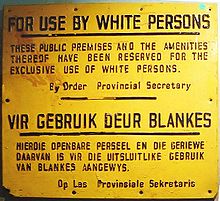

In my high school, Webster Groves, there were a series of ironic things that happened in my history classes. We were reading about socialism and communism and about sharing the wealth, and it seemed so intuitively obvious that that’s how the world should be run. On the one hand we were practicing duck and cover to protect ourselves from the Communists, but on the other hand we were learning how fair those systems are. Webster Groves was a pre-Civil War town that had had plantations and farms with slaves. Every kid knew disturbing history. In my junior year we had a teacher who was new to the area and kind of young. He started out with a lecture about people who had been slaves taking up the names of their owners after the Emancipation Proclamation. We were sitting there, black and white kids, some with the same last names, and we all knew that Johnny’s great great great grandfather had owned Sally’s family way back. We’d known this our whole lives, and the teacher was giving us this huge lecture. We were thinking, Yeah, so what? The teacher asked if there were any questions, and the black kid popped up and said, Yeah, I’ve got the same last name as he does because his grandfather owned mine. The teacher got a horrified look on his face. Apparently the history teacher didn’t know the history of the town he was teaching in. Things were not always perfect between the white and black students. We knew our history and knew that it wasn’t good or kind, but we felt it wasn’t worth dwelling on. Most of the time, we students wanted to move towards more racial equality. These high school lectures followed being taught to sing “Dixie” along with the “National Anthem” all through elementary school. Strange….

The next year we had Modern European History. A woman teacher started the first class with an introductory lecture. This class had about 20% black and 80% white students, with two random Asian students whose parents were professors at the big universities. The teacher lectured that we all came from Europe and that European history is the most important in the world, and on and on. She stopped and my friend Janet raised her hand. Janet has blond curly hair and blue eyes. Janet said, I am a Cherokee Indian, and this history has nothing to do with me, and why did you say that it did? The teacher said, Oh. She quickly started roll call, and she got to the name Janet Bushyhead. Janet raised her hand. She really was a Cherokee Indian and a princess at that. An Englishman had married into her tribe years and years ago, so lots of Bushyhead family had blond curly hair and blue eyes. Her dad looked much more Cherokee but her grandmother and sisters did not. It was a priceless moment. We were bratty sixteen-year-olds in 1967. To see the look on this teacher’s face. The black students were all smirking. Had one of them challenged her, they probably would have gotten sent to the principal. We thought, how can she lecture us when she could look out across the classroom. Maybe you don’t see the sleeper Indian princess in disguise but you could see the diversity that we did have in this small town.

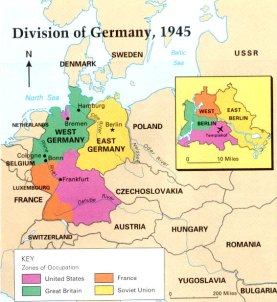

When I was in high school, my dad became the selective service attorney counselor, so that if you were going to get drafted, you were provided with a lawyer to talk to. This was a volunteer post. It was interesting for me; I was a very shy, gawky, geeky sixteen-year-old high school kid and I was watching the sports stars at my school a year or two older than I who had not gone to college or dropped out and now were being drafted and would come over one evening a week. My dad would come home early. I would sit at the top of the stairs where I could hear what was being said. They were almost in tears. I’d listen to what my dad was telling them about deferrals. There wasn’t much hope he could offer them. It was sad, and some of them never came home. This counseling brought it all alive for me, just like World War II later came alive for me when I traveled in Germany. My mother told me a lot of stories about World War II, and watching this unfold in my younger years brought it all home and understand the impact of being in your teens and early 20s during that war was so incredibly major.

My parents started out tolerant of the Vietnam war; it seemed like something the U.S. ought to do. My dad had served in World War II. It made him grow up but it also distorted the rest of his life. In time my family got more and more angry about the war. Both my grandmothers had these big buttons that said “Grandmothers for McGovern” and were very active in his campaign. That’s one of the things that shaped my high school years from 1965 to 1968. The other thing that influenced me was the knowledge that my great great great grandfather had owned slaves, and then, after “Roots” was aired, to see black people come to our house to look up their family histories in the slave book. Then in the spring of 1968 a lot of dramatic events happened. Martin Luther King was killed, and then the night before I graduated from high school, Bobby Kennedy was killed. It was this weird feeling. I can remember we were having our family dinner before we went to the graduation ceremony, and there were these graduate parties afterwards, and I was sitting there all dressed up in those silly clothes, supposed to be celebrating the biggest event of my life, and we’d just had another assassination. It was really hard to reconcile the two: to go forward with the ceremony and the congratulations and to party that night and the assassination the day before. There wasn’t much alcohol and barely any marijuana at this party because it was 1968 in the Midwest. Five years later everybody would have gotten drunk or stoned to mourn the assassination. But it was a real wake-up call that these things were happening my senior year of high school.

Graduating from high school is a big change in your life, but graduating into a world where assassination was becoming an everyday occurrence was scary. What would college and adult life be like? [to be continued]