Laurie Baumgarten first became politically active during the Free Speech Movement at Berkeley. She later taught grades K-8 for 35 years in the Berkeley schools. In the past seven years she has been active in the climate movement, working with the Sunflower Alliance in Richmond, CA, a front-line fossil fuel community. She helped develop a basic climate education curriculum for adults based on the dialogic methods of Paulo Freire, which has been used in over 30 local workshops. Her current political concern is how to incorporate a democratic decision-making structure into organizations as they build a mass movement for change.

Laurie Baumgarten first became politically active during the Free Speech Movement at Berkeley. She later taught grades K-8 for 35 years in the Berkeley schools. In the past seven years she has been active in the climate movement, working with the Sunflower Alliance in Richmond, CA, a front-line fossil fuel community. She helped develop a basic climate education curriculum for adults based on the dialogic methods of Paulo Freire, which has been used in over 30 local workshops. Her current political concern is how to incorporate a democratic decision-making structure into organizations as they build a mass movement for change.

When I came out to California in 1964 from Connecticut to go to the University of California at Berkeley, there wasn’t yet a second-wave women’s movement on campus, but obviously there were foundational things happening that I was not aware of. Betty Friedan had by then written her book, The Feminine Mystique (1963). The whole environment of growing up in the suburbs—the isolation of women there and their infantilization as wives and mothers in these isolated communities—was already giving rise to a kind of despair that she picked up on and wrote about.

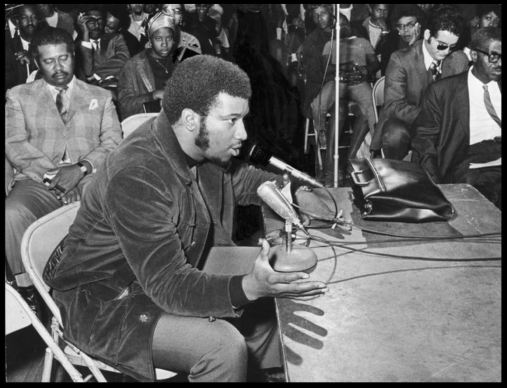

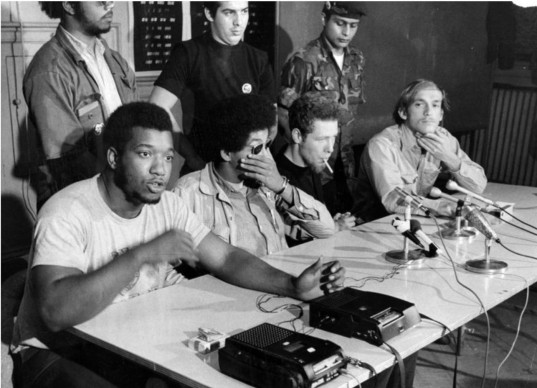

At Cal I got involved in an organization called Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). At that time the Berkeley chapter of SDS was doing a lot of civil-rights organizing on campus, fighting against segregation in various industries in Oakland. Things were pretty segregated in terms of hiring practices at the auto shops and restaurants, so SDS would join with the Black community and picket these establishments on the weekends. While SDS was part of the New Left, and believed in participatory democracy, it was still male-dominated. My feminism grew out of this involvement.

The women in SDS played fairly traditional roles. We were typing the leaflets, getting the refreshments together, and doing a lot of the legwork of running the organization. We would go to meetings, but it seemed that we were essentially there to be playmates for the men. Many of these male leaders were married, and their wives were taking care of the children and putting their husbands through graduate school, but the undergraduate women on campus were being “horizontally organized,” as the joke went. I wouldn’t call it sexual harassment in the way that term is used today, but we were playing a particular role with which we became increasingly uncomfortable; we felt that our own identities were invisible.

I remember one specific meeting at the beginning of a semester, in which it was suggested that the women organize a little auxiliary to bring refreshments to all the meetings. There were a few women, of course, who were not in that mode. There was Bettina Apetheker and some of the women who had played more leadership roles in the Free Speech Movement. But they were kind of masculinized in the sense that they were seen as a little bit oddball up there as women with essentially male leadership.

But I was not coming from that place; I was one of the troops. In SDS, we began realizing that there was something wrong with this picture, that we were not feeling confident in our own abilities to think through political positions within the struggles taking place in SDS. There’d be meetings with votes on various positions and a lot of us didn’t know which way to vote—we would just vote the way our boyfriends did. The roles we played as women were not as full-fledged members of SDS. This unease grew as the struggles within SDS became more intense and the factionalism, which was rampant in the organization on campus, increased.

So a group of us women on the Berkeley campus got together, as was happening all over the country in different contexts, and decided to form a women’s caucus to think through the issues together before the meetings. This was probably in ’65 or ’66. I do remember the first leaflet that we wrote. We decided to go public with it to the students on the Berkeley campus. Its title was: “Do Your Politics Change When Your Boyfriend Changes?” It continued, “If so, join the women’s caucus and let’s talk about the issues.” And so we began meeting regularly in a women’s group; there would be between ten and fifteen of us, mainly women who were active in SDS. We met at my home on what was then Grove Street. We would look at the upcoming agenda and develop our own abilities to think through the issues. We would debate, talk, and try to figure out where we stood on each issue both individually and as a group. That was my first experience with what later became known as consciousness-raising groups. As SDS grew and developed different campaigns such as the SDS Anti-Draft Union, we women stepped up more easily to leadership roles.

So a group of us women on the Berkeley campus got together, as was happening all over the country in different contexts, and decided to form a women’s caucus to think through the issues together before the meetings. This was probably in ’65 or ’66. I do remember the first leaflet that we wrote. We decided to go public with it to the students on the Berkeley campus. Its title was: “Do Your Politics Change When Your Boyfriend Changes?” It continued, “If so, join the women’s caucus and let’s talk about the issues.” And so we began meeting regularly in a women’s group; there would be between ten and fifteen of us, mainly women who were active in SDS. We met at my home on what was then Grove Street. We would look at the upcoming agenda and develop our own abilities to think through the issues. We would debate, talk, and try to figure out where we stood on each issue both individually and as a group. That was my first experience with what later became known as consciousness-raising groups. As SDS grew and developed different campaigns such as the SDS Anti-Draft Union, we women stepped up more easily to leadership roles.

These small, informal, local groups were the backbone of the second-wave feminist Women’s Liberation Movement. They spread like wildfires all round the country, and eventually a women’s movement developed. We would meet and get down to the nitty-gritty of supporting each other—first of all, by reading feminist literature that was coming to the fore, and then defining issues in our lives.

After graduating from college, I became a teacher. A group of us teachers in the Bay Area who opposed the Vietnam War formed a collective called Bay Area Radical Teachers Organizing Collective or BARTOC. The group was multi-gender, and we mainly developed anti-war curriculum for our students, but we also formed as a spin-off of a women’s group to address problems we were having as working women.

I remember one meeting where we decided as a group that we were going to go home and ask our boyfriends to do the dishes. We were doing the cooking and the cleaning, and we were working. We felt we shouldn’t have to cook and do dishes at the same time: we had two jobs and they only had one job. So we decided we were going to get up the nerve to go home, sit our men down, and tell them they should do the dishes. Then we were going to report back how it went. At that time I was living with a man named Dennis. I said to him, You’re going to do the dishes from now on, and he agreed! So we all went back to the next meeting two weeks later, and everyone reported in. Some men were more cooperative than others, but at that point that struggle for the division of labor was primary.

Then there were all the issues of how we were feeling about ourselves—the self-hate, the feelings about our bodies never being good enough, no matter how skinny or how big-breasted, or whatever we were; we realized that all of us hated our bodies—they didn’t meet up to the image of what we thought a perfect body should be. So there was a lot of discussion about that, and about birth control, abortion, and other issues of female anatomy.

It took a long time of meeting in small groups for us to understand that the personal is political. That was the deep message that we were trying to get out: that what was going on in our personal lives had this political dimension, that it was a reflection of our own status in society.

There were struggles within these small “consciousness -raising” groups, of course. There were personal things that came down. Women were divided sometimes. I remember I was at one feminist meeting in which the speakers were dressed very sexily and wore high heels, and my friend said to me, Slaves. They’re dressed like slaves. So there was a lot of judgmental stuff going on, like How come you’re not wearing your overalls? There was one very painful split that happened in our BARTOC group. One woman kept suspecting that another woman in the group was having an affair with her live-in boyfriend. Everyone kept denying it: Oh, that couldn’t be, you’re just paranoid, we’re sisters and sisterhood is powerful, and it turned out that the affair was true. That was painful because sisterhood wasn’t so powerful in that group after all!

There were also political differences and struggles amongst us. There were women who wanted to liberate women only from the confines of gender restrictions. These were more liberal, more reformist women, women who identified more within the Democratic Party. And then there were feminists who were more radical and identified themselves as Marxists. They wanted to do away with the capitalist system. We were all women, but first and foremost we were young people trying to sort out our world-views.

Women like myself who were active in the New Left were fighting for equality for others, but we ourselves were not being respected. Men did not want to give us equal speaking time at rallies and would laugh when women stood up and started articulating a feminist position. It was quite a struggle to change men’s consciousness and for them to get it. And as we know from today’s revelations about sexual abuse, there is deep down in the male psyche a tremendous objectification of us as women. I don’t think all men were equally insensitive. There were clearly some who got it, as Frederick Douglas had in the early suffragette movement when he attended the first women’s convention at Seneca Falls. But most men didn’t—then or now. Even ones who were considered “heavies” in the movement—I mean, some of the most respected of the leftist men, building the student movement, building the anti-war movement at the time, building the Black Power Movement—still didn’t grasp the nature of sexism.

In the early ’70s, I was living in San Francisco with a man who was an activist and with whom I had previously worked on The Movement newspaper, a national SNCC/ SDS paper [SNCC was the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee]. I’d been living with him for nine years and had helped raise his child from a previous marriage since the age of two. I began to realize that this relationship was feeling more and more oppressive to me. I was tolerating a lack of closeness and respect that I did not want to live with anymore. I wanted to break free from patriarchal dynamics. My two closest friends in San Francisco, who also lived with well-known movement men (one had actually written a book on the family and became well-known for it), were also breaking up. The men weren’t getting it, they weren’t changing. Maybe they were changing at an intellectual level, but not in their personal lives.

In the early ’70s, I was living in San Francisco with a man who was an activist and with whom I had previously worked on The Movement newspaper, a national SNCC/ SDS paper [SNCC was the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee]. I’d been living with him for nine years and had helped raise his child from a previous marriage since the age of two. I began to realize that this relationship was feeling more and more oppressive to me. I was tolerating a lack of closeness and respect that I did not want to live with anymore. I wanted to break free from patriarchal dynamics. My two closest friends in San Francisco, who also lived with well-known movement men (one had actually written a book on the family and became well-known for it), were also breaking up. The men weren’t getting it, they weren’t changing. Maybe they were changing at an intellectual level, but not in their personal lives.

There was progress around some of the division of labor issues, but at a deeper emotional level, the men could not grasp something about our interior landscapes and who we were as full human beings—that was, and still is, very difficult for many males. Even if they agreed to do the dishes or share some of the childcare, we were still objects for their pleasure or their needs. We were still supposed to look and act certain ways, be subservient in certain ways. That was certainly true in my relationship, and I wanted to break free from all that. A huge part of my coming into my own was in leaving this guy, whom I had greatly looked up to as an influential leftist. I had gotten some vicarious kudos from being with him. We’d been in study groups together, and he had a certain gravitas because of the role he’d played in the movement. But it was oppressive. I felt stupid, depressed, and self-hating most of the time.

I think I stayed in the relationship so long because in some basic way it imitated the family I grew up in. My mother had internalized a lot of self-hate, too. She wasn’t allowed to fully express who she was. She was supposed to just take care of those kids and get the food on the table. There was a whole artistic side to her which she never got a chance to develop.

It is always painful to break up, and even though I had made up my mind to do it, I felt like I was losing my family, my home and my security. The day I moved out from the our house into a tiny apartment, I said goodbye in the morning. The Black Muslims had a moving service; they were supposed to come and move me. I wanted to be out before 4 o’clock. (He was working in the steel mills and his shift ended about then.) It was getting later and later and the moving truck had still not arrived so I called my friend and said, What am I going to do? And she said, Call them up and tell them they have to get the truck there because your boyfriend threatened to beat you up if you were still there when he got home. So I called them.

Oh, lady, they said, we’ll be right there. Our truck broke down in Oakland; we’re going to get you another one and have you out of there by 3:30. I guess they didn’t want to be responsible for my getting beat up.

So I moved out. That night I had this dream of moving from a dark room into a room full of light and sun. It was sort of a “power dream” about being liberated from the confines of this traditional relationship. That dream kept me from going back. It was so clear when I woke up in the morning.

That dream set me on the path to emotional independence just as my teaching credential had given me my own paycheck. I had freed myself from this oppressive relationship, and I began putting myself at the center of my own life. I would be alone and without a partner for many years, but I became a committed activist. I started writing poetry and reading more feminist literature. I studied tai chi daily, and I built a social network of friends I hold dear to this day. I felt as if the cellophane I’d been wrapped up in all my life was being peeled off. I could finally breathe.

I started linking up with other feminists in San Francisco. I became a good friend of Judy Brady (Syfers) who had written her famous “Why I Want a Wife,” the iconic piece that was first published by the National Organization for Women (NOW) and then later included in the anthology Sisterhood is Powerful. She realized that even though she was married to a leftist, she was cooking and cleaning and sexing and raising the children and chauffeuring and doing all the things that she wished she had a wife to do for her. I also met and became good friends with a woman named Chude Pam Allen, who had written a book called Free Space in which she advocated the strategy of consciousness- raising in small groups. She was the editor of the newspaper for an organization called Union W.A.G.E. which when I joined the group organized working class women into unions and focused on women in construction trades and on downtown clerical workers.

The group had been around for awhile, and many of the younger women in that group like Chude and me wanted to broaden the issues to bring a feminist consciousness into the organization. We wanted to raise issues about the structure of the family, about parenting and marriage, about the role of teachers and nurses. The organization became very divided over how broad or how narrow its focus should be. For example, the gay and lesbian movement was emerging, and some of the women in the construction trades were lesbians and wanted Union W.A.G.E. to essentially be a single-issue organization which would support them in becoming unionized and gaining equality with the men in the trades.

There were also issues with the African-American women with whom we were becoming connected through an African-American social worker and psychotherapist on the East Coast named Patricia Robinson. She had been a founding member in 1960 of the seminal Mount Vernon/New Rochelle women’s group composed of poor and working class Black women—often single mothers—who had published their important work called Lessons From the Damned about class struggle in the Black Community. Through Pat we began to anonymously share across ethnic and class differences the letters and essays and poems that we were all writing to our fathers and brothers and husbands and sons as we struggled to understand how the patriarchy was coming down in our lives. Chude, as editor, turned over one issue of the newspaper to the Black sisters of New York to have as a voice for themselves. Many of us supported that move. But some of the trade-unionist and narrowly- focused women were furious that Chude would give over the editorial control of our newspaper to a group of outsiders. Eventually Union W.A.G.E. fell apart over these conflicts after decades of a long and reliable history. Lots of things were coming to an end. Organizations come and go.

The group of us in W.A.G.E., who were trying to build a broader base in San Francisco formed a readers’ theatre called Women’s Words. Women’s Words put together readings in coffee houses based on the poems and letters we were all sharing. We would speak the words of women confronting their families about how they felt. We often included excerpts from earlier struggles, from women fighting in the Labor and Suffragist Movements. These readings flowed back and forth from highly personal stories to deeply impassioned, political narratives.

Pat Robinson was an early Marxist feminist and had been connected with Chude through Chude’s first husband, Robert Allen, the editor of The Black Scholar. Pat was helping women, including myself, deal with how we negotiate, how we function in this patriarchal world that we find ourselves in, in terms of being married or not, having children, working for a living, etc. We would talk to her on the phone, visit with her when we were back East and write her letters, and she would respond as a clear-thinking mentor and therapist.

Finally I confronted my father personally. Robinson felt that if your father were still alive, you had the opportunity to confront him directly. To stand up and own yourself to your father was one way to move beyond that internalization of the patriarchy that we had acquired growing up. So I felt the need to confront my father after an incident at work in which I had been intimidated by my boss.

I was a fifth-grade teacher in the Berkeley public schools, and I was being called on the carpet for not using the mandated spelling program. It’s absurd when I think back on that stupid program that they were using for spelling. It just wasn’t right linguistically; it made no sense. It was some kind of fad that had gotten sold to the district. I refused to use this program so I was considered insubordinate. I knew there was another teacher at the school who was highly respected—years earlier she’d been my master teacher—and I said that she wasn’t using it, either, thinking I could gain a little bit of “cred” using her name. Immediately I realized that I had done a terrible thing by mentioning her. I felt horrible and ashamed. I went home and wrote to Pat, saying, Oh my god, what was this about, and how could I do something like that?

I was a fifth-grade teacher in the Berkeley public schools, and I was being called on the carpet for not using the mandated spelling program. It’s absurd when I think back on that stupid program that they were using for spelling. It just wasn’t right linguistically; it made no sense. It was some kind of fad that had gotten sold to the district. I refused to use this program so I was considered insubordinate. I knew there was another teacher at the school who was highly respected—years earlier she’d been my master teacher—and I said that she wasn’t using it, either, thinking I could gain a little bit of “cred” using her name. Immediately I realized that I had done a terrible thing by mentioning her. I felt horrible and ashamed. I went home and wrote to Pat, saying, Oh my god, what was this about, and how could I do something like that?

And I realized it was my fear of authority, my fear of getting in trouble, and that in some way my intimidation dated back to my fear of my father, who had been an authoritarian, and that I had grown up and still was frightened of him. He was passive-aggressive, but still he was a well-meaning man. He was born in the U.S. to a poor, German-Jewish immigrant family. His father had been a roofer. He grew up in the Bronx, worked his way up by going to night school, and became a lawyer. After marrying my mother, he moved his family to the suburbs because he wanted his children to grow up in fresh air. He worked very hard, was never a wealthy man, but his home in Connecticut was his castle, and he was proud of his upward mobility. I had always been intimidated by him.

Through my work with Pat, I came to believe that my intimidation of the principal had to do with this internalization of the patriarchy through my father. Pat was working with women in the movement who were struggling to stand up to the system, to stand up to the “Man”—the internalized Man and the real Man. How do we find the strength and the power within ourselves? For women that often meant taking on the father figure.

So I wrote a letter to my father. I said I thought he had been fascistic towards me growing up. And he had been in the sense that I was scared, and he used to yell at me and make me feel I didn’t have freedom to be myself or express how I was feeling. He was controlling. He was that way with my older sister, too, but I think I was more of a rebel at home than she was, and so I somehow triggered more of an authoritarian response. I had been the easier scapegoat for his anger, as I did not look like or sound like the successfully and fully assimilated Jew. He disapproved of my friends and the type of bohemian crowd I was drawn to. He tried to keep me from seeing these friends, and there was no way to talk through or negotiate our conflicts. So I wrote him this letter where I told him I’d been frightened of him, he’d been oppressive, that he hadn’t considered my feelings.

My mom was kind of his lieutenant. She went along with his ultimatums and did not defend me. She was a typical housewife. I’ve come to understand her strengths and skills, but she was basically a suburban housewife, and of course her livelihood was through his paycheck. He would dole out an allowance, from which she had to manage the household. She didn’t have her own paycheck, which immediately puts a women at a terrible disadvantage. By the time I confronted my father, I was earning my own living. I didn’t want to “be like my mother” and be dependent on a man, so I was happy when I became a teacher and got my own job. It was such a relief to know I could support myself in the world and would never have to be dependent on my father or on a husband.

My father was furious with my critical letter. For two years he didn’t speak to me. He was hurt that I called him a fascist, which was the worst name you could call someone who was Jewish. I regret it now and realize I could have toned it down a little. Finally he did speak to me again. I went home to visit at one point but the confrontation continued because something I said triggered a furious reaction, and he started screaming at me, and I said, don’t you ever scream at me like that again. Fuck off. He picked up a chair!

He had never hit me—my mother did some of that—but he picked up a chair and came at me. He was so enraged that I’d stand up to him in that way, and I just looked at him. He stopped, and—this was a most embarrassing moment—he got down on the floor and started kicking and screaming like an infant! I couldn’t believe it! My mother came running into the living room and said, What have you done to your father? What have you done to your father?

Now my father was a dignified man, a well-respected lawyer; he was on the school board, he was brilliant, had worked his way up by getting all the awards from the public schools in New York, and now he was down on the floor. A shift occurred in me when I saw that. He was internally dethroned. I began seeing him as a kind of vulnerable human being who’d suffered a lot of anti-Semitism, a lot of pain in his family; he was a traumatized individual, who had worked his butt off for his kids. His masculine power was a bubble that had burst. It was a paper tiger. The next day he was driving me to the airport to return to California, and it was strange but I do remember this kind of opening in my heart toward him, and I think I felt love for him for the first time. I felt a softness toward him that I’d never felt before because I’d been so frightened of him. You can’t love somebody in a deep way if you are scared of them. This confrontation of our parents and confronting the male authority that we had so internalized was part of the process that many of us were going through to become stronger, more liberated, for ourselves and for our children. We had been inculcated with patriarchal and hierarchical power relationships in our childhoods that had left us feeling helpless, and we were determined to overcome them.

I eventually moved back to Berkeley and got involved in the anti-nuclear struggle with the Abalone Alliance. This state-wide network organized a massive civil disobedience of Livermore Lab with 1600 arrestees. It relied on small affinity groups and feminist process. And when I went to jail with my comrades, I never thought for a minute about whether my father would approve or not!

Laurie and her husband Michael today

Tags: 1960s, 60s, 60s and 70s, authoritarianism, BARTOC, Bay Area Radical Teachers Organizing, Berkeley, blog on the sixties and seventies, Cal, Chude Pam Allen, family, feminism, Free Space, free speech movement, Lessons from the Damned, oral history, patriarchy, Patricia Robinson, protest, sixties, student movement, UC Berkeley, union organizing, Union W.A.G.E., Why I Want a Wife

. Forrester grew up in Los Angeles during the conflicted 50s and tumultuous 60s. A graduate of the MFA Bennington Writing Seminars, her essays and short stories

. Forrester grew up in Los Angeles during the conflicted 50s and tumultuous 60s. A graduate of the MFA Bennington Writing Seminars, her essays and short stories have appeared in multiple publications. Her debut memoir, Guns Under the Bed: Memories of a Young Revolutionary, revolves around the time when she was a member of the communist Revolutionary Union (R.U.), an organization formed in the late sixties. Their ideology was based on the theories and practices prescribed by Mao Tse-Tung, the chairman of the Chinese Communist Party.

have appeared in multiple publications. Her debut memoir, Guns Under the Bed: Memories of a Young Revolutionary, revolves around the time when she was a member of the communist Revolutionary Union (R.U.), an organization formed in the late sixties. Their ideology was based on the theories and practices prescribed by Mao Tse-Tung, the chairman of the Chinese Communist Party.

, Maria Dolores and I walked behind an old man wearing much-laundered cotton pajama pants without a shirt. Scarred pockmarks pitted his back and chest. Exhilarated, I took mental photographs of those walking with us: whole families, big sisters and brothers carrying the youngest, the stooped elderly, babies strapped onto their mother’s chest with wide strips of cloth, little girls and boys on the side chasing each other, some kicking a soccer ball, others competing in a game of stickball. Sweating bottles of soda, free for the taking, sat on blankets shaded by brightly striped beach umbrellas where the youngest and oldest rested.

, Maria Dolores and I walked behind an old man wearing much-laundered cotton pajama pants without a shirt. Scarred pockmarks pitted his back and chest. Exhilarated, I took mental photographs of those walking with us: whole families, big sisters and brothers carrying the youngest, the stooped elderly, babies strapped onto their mother’s chest with wide strips of cloth, little girls and boys on the side chasing each other, some kicking a soccer ball, others competing in a game of stickball. Sweating bottles of soda, free for the taking, sat on blankets shaded by brightly striped beach umbrellas where the youngest and oldest rested.