Roselva Rushton Ungar is a retired teacher, 86 years old. She is currently writing a memoir. She has authored a history of union organizing in the early childhood/Head Start field and written extensively on educational issues such as bilingual education, scripted reading programs, and high-stakes testing. Born in Detroit, she grew up in Russia and returned to the U.S. for college. She helped build the Early Childhood Federation, Local 1475 AFT. Most of her adult life has been spent organizing around social justice issues such as campus free speech, civil and women’s rights, defense of immigrants, and a sustainable planet.

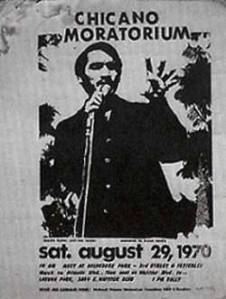

[Editor’s Note: “The Chicano Moratorium, formally known as the National Chicano Moratorium Committee, was a movement of Chicano anti-war activists that built a broad-based coalition of Mexican-American groups to organize opposition to the Vietnam War. Led by activists from local colleges and members of the “Brown Berets”, a group with roots in the high school student movement that staged walkouts in 1968, the coalition peaked with an August 29, 1970 march in East Los Angeles that drew 30,000 demonstrators…. Laguna Park is now Ruben F. Salazar Park.” Source: Wikipedia]

Part 1 of 2

It was August 29, 1970, a warm, sunny day in Laguna Park. Birds had taken refuge in the trees, waiting for scraps from family picnic baskets. Free sandwiches were provided by “green power,” a youth environmental group. A couple of booths had literature. An anti-war march scheduled for Whittier Boulevard was to end at the park. I was with several teacher friends from eastside Head Start schools, who’d decided to go directly there for a pleasant afternoon and to support the community in which we worked. Ominously, some UCLA medical students were staffing a first-aid center at the park building.

We sat down on the grass near the front and listened to music and a Puerto Rican drum group, watched children in traditional costumes dancing folklorico. Hot dogs were passed out, cakes and Kool-Aid. The park was crowded; people sat very close to each other. Children, babies, elderly people—everyone in a happy picnic spirit, festive and relaxed. We were all watching the program, applauding and occasionally shouting Viva la raza!

The march of mostly young Chicanos protesting the war joined us at the park chanting Raza Si, Guerra No as they entered, bringing the crowd to over 30,000. Many of these people had been activated by the “blowouts,” when Lincoln High School students walked out in 1968 led by Salvador (Sal) Castro. The year before there had been Viet Nam Moratoriums all over the country and a National Student Strike to stop the war, but not much had been organized against the war on the east side of Los Angeles. These were patriotic people who had sent their sons off to the armed services as a matter of course. But as it became clear that proportionately much higher numbers of Latinos were coming back in coffins or badly injured, it was time for them to speak out.

Speeches from the stage expressed community outrage. Rosalio Muñoz, UCLA student organizer and co-chair of the event, was speaking when we heard people behind us turning to look at a disturbance. People stood up to see better. The platform speaker and monitors told us to stay seated and not leave, No se vayan.

Within seconds, I heard the cries, La jura, la policía. The police are coming. Bottles sailed through the air. People stampeded toward the platform. A monitor urged us to go home. I headed in the direction of Whittier Boulevard but was jammed up against the platform and the buses parked along the street. In the center of the park was a wide clearing; people ran and walked toward the periphery at Eastern Avenue.

Buses pulled out. I headed toward Whittier Boulevard when I saw a woman and a small boy crying. A man said she’d been maced after getting off the bus. He held one arm and I took the other to guide the woman and child to the first-aid center. There I helped her wash out her eyes with a hose and tried to reassure her in Spanish. Inside the center several young men were being treated for wounds. An ambulance finally came but took only wounded officers.

Many others arrived with stinging eyes and bloody heads so I stayed to help. As I worked there at the hose, the police sprayed us with more tear gas! It stung my eyes and face and made me dizzy. I washed my eyes out; fortunately only a small amount had landed on me. Gas was directed at the park center, which served as a first-aid station. Both doors were clouded with gas, sprayed from the ball park and from the patio on the opposite side. Some men from Physicians for Social Responsibility tried to go collect the lost and injured, but the gas was too strong.

A young man with a badly bloodied head, which a doctor had bandaged, urged me to call his family to come pick him up. I started for the office where there was a phone, but the police had closed off the park around us and there was violence along the edge. In the next room I saw lost children and mothers, who had somehow ended up here rather than being swept out of the park, looking for their families,.

I offered to bring my station wagon close to the park as soon as possible to evacuate some of the wounded. A young doctor, who appeared to be in charge, sent me with a young woman Marilyn, who had been working with the medical group, to get my car. We started out on foot, only to run into two police officers who waved their clubs and shouted, ”Out of the park.” I explained that we needed to get my car to carry out the wounded. “Not through here!” he admonished. “That way.” He pointed toward the corner of Eastern and Whittier. That was not the direction I needed to go to get my vehicle, but there was no arguing with an angry bully waving his club and holding a tear gas canister. My companion Marilyn ran back to the center to get armbands to show that we were a medical team. I walked slowly in the direction indicated, hoping she would be able to catch up with me.

While I delayed, I saw four policemen roughly shoving a man who was staggering and obviously unable to see where he was going. “He’s been gassed,” I said. “Let me take him to the first aid station.” They ignored me and continued shoving him. I was scared and thought, Why are they doing this? It was a contemptible way to treat a human being, whether guilty of anything or not. He was young, Latino and completely helpless, at the mercy of four strong policemen who continued to push him toward Eastern Avenue. Why weren’t they knocking me around? Was it because I was an older white woman?

We walked a few blocks to the car, seeing hundreds of mostly sheriff deputies around the park, at corners and blockading the streets. We decided to drive a block south of the park, but because of traffic problems, blockades, and difficulty getting back across the freeway, it took 45 minutes to return. As we drove we saw people standing along Whittier looking grim and angry at the invading police; store windows were smashed and angry youths ran to escape. Someone screamed at us, Get out of here, so we realized we had better identify ourselves. Two white faces probably looked like intruders in this barrio under siege. Without stopping, I had Marilyn quickly remove my first-aid book, which had a large red cross on the cover, from the glove compartment and place it on my front windshield. I drove as fast as I safely could through the threatening crowd, then stopped a moment to fasten one of the armbands to the car’s antenna. As we neared the park, we were detained by officers at each corner and forced to turn back and seek another route. In some cases, we were able to talk our way through the blockades. Driving down a side street we encountered a young man with an army armband directing traffic. He escorted our wagon along the block near a burning car. Just in time we were shunted off into an alley as the car exploded with a terrific blast. Fragments flew everywhere. People came running out of their homes toward the alley as other popping sounds occurred; whether guns or other explosions, no one knew. We had to get out of there and back to the park.

[To be continued….]

This is an AMAZING and very thoughtful site. Thank you for your work! Are you interested in reviewing a book on growing up in the ‘60s and ’70s? I’ve discounted my coming-of age-novel Ride the Snake (author Kevin Kelly) to FREE on Amazon as a Kindle download for the long weekend. Thanks for checking out the madness, and possibly reviewing the book!

LikeLike

Hi Kevin, glad you like the site! I’d love to review your book. I will download it tonight. (If you get a chance, you might like to review mine too, especially if you enjoy fiction.)

LikeLike

I would be happy to review your book. I’ll get on it forthwith.

LikeLike